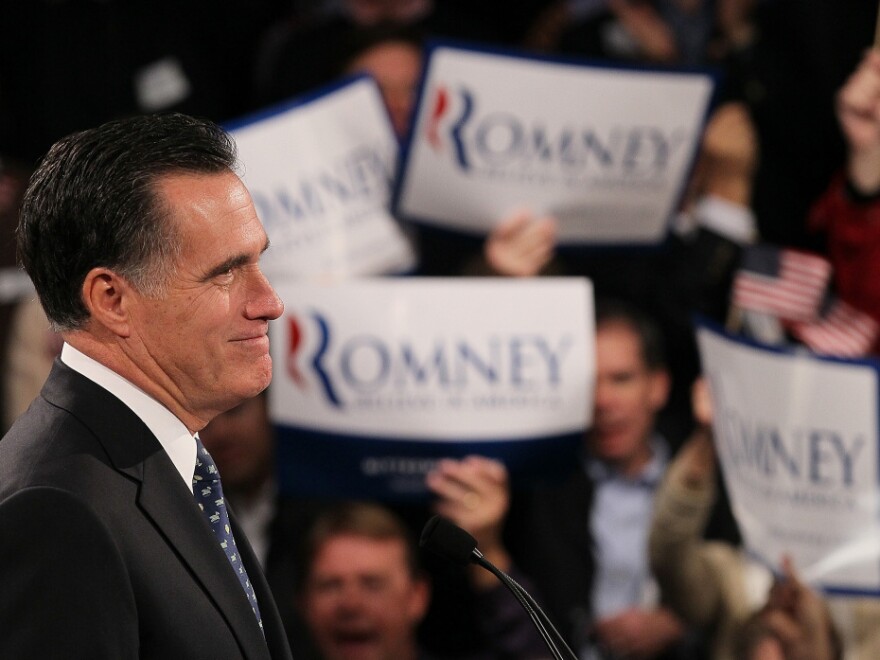

Even as he claimed victory in the New Hampshire primary Tuesday, Mitt Romney fired a defensive salvo against Republican rivals who have begun to question whether he made his fortune at the expense of U.S. workers.

"The country already has a leader who divides us with the bitter politics of envy. We have to offer an alternative vision," Romney told supporters in Manchester, N.H. "I stand ready to lead us down a different path, where we're lifted up by our desire to succeed, not dragged down by a resentment of success."

But Randy Johnson, who lost his job at an Indiana paper company after Romney's investment firm, Bain Capital, bought the company's plant in 1994, has been loudly criticizing Romney and his methods.

"He made money — if that was his goal — he made a lot of bucks," Johnson, who has been shadowing Romney on the campaign trail, told reporters in Iowa. "Is that what we want? People that are worried about money more than the workers?"

Private Equity

The scrutiny has also shined a spotlight on the lucrative business known as private equity, where Romney made his fortune. Steve Judge, who heads a private equity trade group in Washington, D.C., says the business model is pretty simple: "We buy companies that have significant potential for growth, either because they have great promise or because they need to be turned around. We invest capital and effort and expertise to improve their performance and hopefully increase their value."

There are a number of ways to do that.

A once-neglected company like Dunkin' Donuts might use an infusion of private equity money to grow, open new stores and hire new workers. That's a win for everybody.

But Colin Blaydon, who heads the Tuck Center for Private Equity and Entrepreneurship at Dartmouth College, says sometimes boosting value can also mean cutting costs.

"You might ask your employees to take lower pay. You may shift the jobs somewhere else. You may replace people with robots," he says.

In that case, the gains are not so widely shared.

Private equity firms can also multiply their profits through "financial engineering," borrowing most of the money to buy a company, then quickly recouping their own costs through dividends and management fees.

It's a bit like a homeowner who puts $5,000 down on a house, then quickly withdraws $10,000 on a home equity loan.

Howard Anderson, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, says some companies crumble under the resulting debt load.

"Sometimes a company couldn't sustain the debt and they had already taken money out," he says.

Bain's Record

In fact, of Bain's top 10 investments, four of the companies ended in bankruptcy. But Bain still walked away with more than $500 million in profit.

Former House Speaker Newt Gingrich told Fox News that doesn't sound like the free market.

"It's one thing to say, look, if a company has failed despite your best efforts, and you've put money into it and you take a loss right along with all the workers, that's free enterprise," he said. "But if the rich guy's taking all the money and the working guy's being left an unemployment check, that's not sound, healthy capitalism. That's the kind of thing that I think frankly makes people very suspicious of Wall Street."

Judge says firms like Bain could not survive if they routinely drove companies into bankruptcy.

Dartmouth's Blaydon adds that while private equity's bare-knuckle cost-cutting may be painful, it's really what any good manager should do.

"That's what we want in our economy, if our economy is going to be more valuable and more competitive," he said.

But workers like Johnson aren't so sure. Bain Capital made more than $100 million off his company, even though the plant shut down and the company wound up in bankruptcy.

"To this day, I still don't understand why people think that making profit over good jobs, helping communities, families — at what point does the profit take control?" he said.

That's a question Romney's rivals will be asking in South Carolina, where the unemployment rate is near 10 percent, and where a superPAC supporting Gingrich has threatened to spend millions on anti-Romney advertising.

And if Romney wins the GOP nomination, it may be a question voters are asking in November.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.